BY LETTER

Menexenes

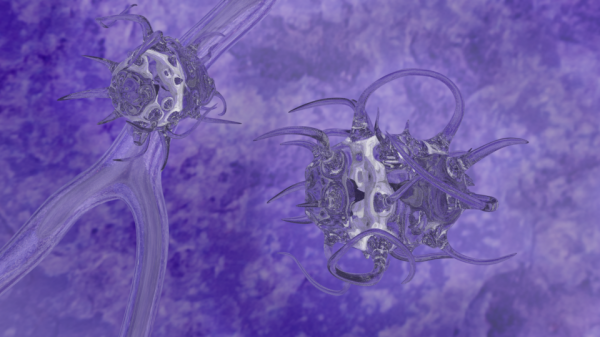

Exotic lifeforms existing in the metallic hydrogen core of a gas giant world | |

Image from Liam Jones | |

| Two Menexenes float far below the hydrogen ocean layer, with a Worldtree in the background (magnetosensory imagery converted to visual analog ) | |

Introduction

The Menexenes are a xenosophont species that inhabit the metallic hydrogen core of an ammonojovian planet in the Socrates 471 system. Their biology is unique in the Terragen Sphere, being based around resistive magnetohydrodynamics rather than any sort of conventional chemistry.Discovered in 8862 AT by the Paideian Mission, the main Menexene system was placed under the protection of a Caretaker God by its inhabitants' own request in 9300. However, in the intervening centuries, some Menexenes travelled off-world using specialised engenerators. They and their descendants are currently colonising a number of systems in the Auriga sector.

'Biology'

In the immense pressures and temperatures inside a Jovian planet, hydrogen changes phase to become a dense liquid metal. Physically, liquid metallic hydrogen is governed by the equations of resistive magnetohydrodynamics. Rather than conventional biochemistry, magnetohydrodynamic interactions are the basis for life in Menexenos.Lifeforms consist of complex self-replicating patterns of electromagnetic fields, eddy currents, and fluid flows. A primitive, well-known example is there spheromak — but Menexene life uses far more complicated arrangements.

Impurities dissolved in the hydrogen also play an essential role in Menexene biology. The most abundant impurity is helium, but carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, neon, silicon and sulphur all play essential roles. At the temperatures and pressures of Menexene environment, only the noble gases — helium and neon — are not ionised. Convention currents in the core prevent these heavier elements from separating out. The environment is too hot to allow the formation of molecules. By mass, Menexene life tends to be 72% hydrogen, 26% helium, with the remaining 2% divided among other impurities.

When present in varying concentrations, impurities affect the resistivity and MHD properties of the metallic hydrogen. In turn, MHD structures can separate the impurities by centrifugation or electrostatic fractionation. Further, dissolved helium may reach saturation and precipitate out, further complicating biological pathways. All Menexene life uses feedback loops of this kind. Varying concentrations can be maintained by magnetic bottles, biconic cusps, or more complex structures.

The second essential factor in Menexene biology is velocity and length scales. The magnetic Reynolds number (R_m = velocity scale*length scale/magnetic diffusivity) governs interactions between the magnetic field and the fluid. For R_m>>1 (in other words, large velocities and length scales), the behaviour approximates ideal MDH, with magnetic fields lines frozen into the fluid flow. For small R_m<<1, fields lines are less tightly bound to fluid flow and energy transfer through magnetic reconnection is more likely. (In metallic hydrogen, with a conductivity of 5*10^5 S/m, and assuming as average velocity of 1 m/s, these length scales occur on the order of a metres or less.)

All lifelike systems have metabolisms: The transduction of energy to maintain a non-equilibrium system. Instead of chemical energy, Menexene life uses the energy bound up in magnetic tension to drive its metabolic processes, which is released by magnetic reconnection to create kinetic and thermal energy.

Ecology

The Menexene ecology is governed by the geodynamo system in the core.The fundamental energy gradient inside a gas giant comes from the Kelvin-Helmholtz mechanism: as the planet contracts, it releases heat, which radiates from the core outwards and induces convection currents in the liquid metal hydrogen core. Coriolis force from the planet's rotation splits the convection currents into rolls, which in turn generate eddy currents that create the planet's magnetic field.

There are two separate kingdoms of producers: Electrotrophs gain energy from immense eddy currents. They typically have kilometre-long filaments held together by braided magnetic fields which group together into large branch structures. In contrast, Kinetrophs grain energy from the physical fluid flows. They typically have structures like giant sails that twist and flex against differential currents. Many electrotrophs and kinetrophs live together symbiotically.

Chemical interactions are fundamentally limited to the molecular scale. MHD processes have no such limitation. Consequently, there is no equivalent of microscopic monocellular life in the Menexene ecology. In fact, the simplest and most primitive organisms reach sizes in the range of tens to hundreds of kilometres, with internal structure on the level of decimetres. Later organisms evolved to take advantage of smaller scale interactions, and could consequently become smaller and more internally complex.

Primary consumers — animals — feed by hijacking the magnetic energy storage of autotrophs, either by inducing magnetic reconnection (which produces fluid flows that can then be fed upon) or by linking to eddy currents. They may also consume stocks of impurities.

Helium and neon play an essential role in Menexene bioenergetics. These are the only elements not ionised at Menexene temperature and pressure. Hence they are immiscible in the metallic hydrogen. They are usually stored as emulsions. However, they can also form an insulating fluid membrane. Menexene life uses helium/neon membranes as capacitors to store energy. (Conversely, without capacitors, life would have to store energy in the form of eddy currents, severely limiting its growth.)

MHD systems are relatively delicate compared to chemical systems. Organisms can be disrupted and killed by strong currents, or even fast contact with other organisms. So one of the most important developments of Menexene life is the pallium/viscera distinction. Complex organisms are separated into two layers: The viscera sit at the organism's core, surround by the pallium. The viscera hold the organism's essential functions, such as energy storage, core metabolic systems, structural magnetic fields, and brains. The pallium, meanwhile, is a set of fields and flows generated by the viscera. It has no independent existence. Without the viscera it would quickly disperse; and, most importantly, it can be disrupted with no harm to the organisms. Thus it serves as a buffer, protecting the viscera from harm. Beyond that, it also is used as a sensory organ for different modalities, a display for social interaction, a weapon, and a manipulator.

There is no firm boundary between the pallium and the external world. Rather, there is simply a region in which the organism's control over the magnetic fields drops away. If two organisms come close enough, their pallia can merge: At the intersection, both will have partial control over the magnetic field. Sharing pallia allows a high-bandwidth form of communication.

As an evolutionary milestone, the pallium is perhaps comparable to the eukaryotic cell or multicellularity on garden worlds: Nearly all complex organisms, producers and consumers, have pallia. The main phyla all have distinct pallium specialisations.

Important species

Worldtrees dominate Menexene ecologies. They are branching and webbed structures following field lines for thousands of kilometres, channelling and diverting fluid flows on a planetary scale. They are in fact a colonial species, composed of a large, primitive electrotroph in symbiosis with a variety of more advanced kinetrophs. Because of the simplicity of the larger organism, worldtrees can survive being broken apart by convection currents with — the individual elements simply reconnect with each other when things settles down. The kinetroph species produce flying "smoke ring" seeds that serve as a food source for other animals.Termite-snakes are colonies of long, thin animals that live deep in the worldtrees' pallia and protect it from invasion by other animals.

Blobhives are colonial organisms made up of many thousands of smaller animals permanently sharing a pallium. While the constituents are less than 50cm across, the hive itself can reach hundreds of metres across, and incapacitates larger animals by engulfing them.

Lone-spinners are from the same family as the Menexenes themselves. They look almost identical, though the motions of their pallia are rather less complex, but are largely non-social hunters. Several provolved versions have been made since the diaspora.

Physiology

Evolution

The Menexenes evolved in a unique niche somewhere between social spider, beavers, and parrots. This class of animals developed the ability to generate long, threadlike structures from their pallia that could be used to entangle and ensnare smaller and nimble prey. Some of these in turn developed social strategies where they connected their webs together to form single structures used for protection and communication.The early Menexenes had food sources, including the flying smoke-ring seeds of the worldtrees to the symbiotic termite-snakes living inside the worldtrees' pallia. They learned to use their webs in ever more sophisticated and complex ways. The combined pressures of complex social relations and web usage led them towards sophonce.

Anatomy

The Menexene viscera is an elongated ellipsoid structure some thirty metres long and twenty-two metres wide, with a mass close to a thousand tonnes. The pallium, a dynamic and constantly changing structure, is harder to pin down. It appears jagged — a mass of irregular spines, curved and twisted by the complex magnetic field lines. At the closest approach, it may be a little as 2 metres thick; the longest spines can reach as far as twenty metres from the viscera.Discounting the asymmetric structure of the pallium, Menexenes have order twelve radial symmetry. Though they have no distinction between front and rear, the two ends are distinct. One end, called the spinneret, is slightly more pointed and dedicated to generating threads from the pallium. The other, called the face, is more rounded and dedicated to feeding and reproduction.

The viscera is divided up into specialised regions called organs — though again the connection with Terran organs is tenuous at best. The outer layer of the viscera is a layer dedicated to capacitance organs and generators — complexes structures of current flows and knotted field lines that generate the structure of the pallium, and also receive sensory information from it.

The spinneret contains specialised generators for creating web threads.

The face contains other specialised generators that give rise to feeding manipulators, plus a second set specialised for reproductive interactions. Beneath these are a set of primary energy storage and impurity-separation organs (a stomach of sorts), the reproductive organs, and a copy of the genome (which, for Menexenes, is a macroscopic structure).

Beneath the generators are a set of metabolic organs that distribute energy and impurities throughout the body. Finally, at the core of the viscera sits the brain.

The fundamental element of Menexene web is a thread twenty to sixty centimetres across, centres around densely braided magnetic field lines sustained by inbuilt capacitors. The magnetic field lines allow slow fluid flows to pass with minimal resistance, but provide a strong barrier to fast objects. Additional structures build into the webs can release electrical discharges that incapacitate prey and complexes of field lines that bind threads together into webs.

Webs themselves are complexes of threads. In modern Menexene civilisation, webs can be many tens of kilometres across. For all the difference in environment, some Menexene webs resemble Earth spider's webs in gross structure — a notable instance of convergent evolution.

Locomotion

Being composed mostly of ionised matter, Menexenes find it easier to move parallel to magnetic field lines than across them. They are capable of transverse motion, of course, but it is more tiring. Moving too fast across dense field lines can be dangerous or even fatal, inducing currents which disrupt their internal structure. Consequently, very dense bundles of field lines, such as those found in worldtrees or webs, function as an effective barrier.Menexenes have two primary means of locomotion. The first is "crawling", where they grip a a structure or other set of field lines with their pallium and push along it. The second is "swimming", where they use the pallium as a MHD pump to generate jets of metallic hydrogen. Their maximum speed is 4 m/s parallel to field lines and 0.7m/s perpendicular to field lines.

Senses

The metallic hydrogen interior of Menexenos is completely opaque. However, it does support a wide variety of plasma waves that vary depending where they are based on transverse or longitudinal oscillations , and whether they travel parallel or perpendicular to magnetic field lines.Menexenes can sense all of these. However, they are most sensitive to Alfvén waves (transverse waves of field lines and ions oscillating together, travelling parallel to the field), pure acoustic waves (ions oscillating parallel to the direction of motion), or magnetosonic waves (hybrids of the above). All are active senses: An individual can generate all of these plasma waves. Together, they allow a Menexene to build a clear model of its environment, including magnetic and electric fields, electric currents, and fluid flows. In this way, these combined senses are equivalent to sight or echolocation.

The Menexene sensorium is rounded out by sensitivity to electric currents, magnetic and electric fields, touch (direct contact of the pallium with other structures) and smell (picking out variation in the quantities of impurities).

Plasma waves also serve as the primary medium for Menexene language, though some cultures have also developed touch or magnetic languages for close-range communication.

Lifespan and reproduction

The Menexene genome stores information in chains of magnetic bottles which hold different quantities of impurities, plus a complex set of MHD structures that can read the contents of the bottles (by measuring their resistivity) and reproduce them. The genome is effectively diploid, with two variant copies, and analogues to alleles. Unlike chemical genomes, the structure is macroscopic. An organism usually holds fifteen to thirty copies of its genome in different regions.Mating is a slow, complex procedure in which the two partners, facing one another with the mouth end, slowly share deeper and deeper layers of the pallium. Any misstep by either individual may cause the other to retreat, after which the couple will need to try again (retreats occur in little over a third of attempts). The entire process takes one to two hours. Once the viscera meet, the male transfers a haploid copy of the genome immediately, and the individuals separate.

If fertilisation is successful, the offspring develops in the inner layer of the mother's pallium, in direct contact with the viscera. As it matures it detaches from the viscera and migrates outwards through the pallium. In the second stage of of gestation, the offspring is capable of leaving the mother's pallium for short periods, but returns for feeding and care. Finally, the offspring is big enough to detach entirely. The first stage takes one month, and the second stage an additional one and half months. Upon permanent separation, the offspring is approximately seven metres across. Childhood lasts a further nine years.

Menexenes tend to be promiscuous, taking multiple partners over the course of their life (though some cultures practice varying degrees of monogamy or permanent polygamy). Nevertheless, a great deal of trust is required on both sides for the act. In turn, partial sexual interaction between individuals of any sex is an essential part of social bonding in many cultures.

Environmental requirements

To a Menexene, even a To'ul'h environment is a frozen near-vacuum. They require temperatures and pressures strong enough to maintain liquid metallic hydrogen — usually in the region of 10,000K and 200GPa (2 million atmospheres). A strong magnetic field is not strictly necessary, but such fields are always present in the cores of gas giants.Should the temperature or pressure rise too high, helium and neon will ionise. The Menexene will lose eir capacitance, and die immediately. This upper limit prevents all but the simplest Menexene life from reaching the core.

Psychology

Menexenes live in a very different environment to any on Earth, and their psychology has evolved in line with this fact. There are no solid objects. Continually changing magnetic fields, electric currents, and fluid flows are ubiquitous. Everything, even their own bodies, is made of the same liquid. Other objects shift and flow over short timescales, and decay over long timescales.They have a fundamentally different mental ontology. While humans tend to categorise the world in terms of objects and relations between them, Menexenes see dynamic systems, processes, and continua. Context is always essential to something's nature. To define something in Menexene terms is to specify its internal structure and behaviour.

They are capable of understanding single objects of course, but naturally see such things as isolated subsystems, broken free of spatial and temporal context, rather than entities in their own right. The main use of single-object ontology is in the social realm, where individuals clearly do exist. (When the Menexenes discovered ions and electrons, they drew social metaphors to create the scientific terminology.)

Menexenes of course have an intuitive sense of the complexities of electromagnetism and fluid dynamics. More generally they are good at intuiting the behaviour of nonlinear systems with many variables and complex feedback loops. (On the other hand, they are rather worse at working with abstract logical categories.)

One small but obvious area where this worldview is demonstrated in naming conventions. Menexenes tend to name entire systems in relation to one another, then derive sub-names from that. For example, the Menexene global transport network had a name (roughly translated as "Enemy of non-integrated pallia"), with each separate mode having a name derived as various poetic additions, and the systems of individual cities derived on step further.

A Menexene doesn't see xemself as an object apart from the world, but more of a locus, an integral node participating actively in many systems. The notion of free will in opposition to causality was never an issue in Menexene thought. Similarly, they have an easier time recognising non-unitary nature of the individual. This is not to say that Menexenes are never egoistic or lack individualistic philosophies. Rather, they more readily accept the idea of the individual as a collection of sometimes divergent, contradictory drives.

Given their penchant for dynamics, one may think the Menexenes value harmony. In fact, very often the reverse is true. The Menexenes have a strong aesthetic appreciation of, and appreciation for the importance of, discordance. As a mental archetype, it tends to represent greater complexity, an opposition to monolithic ways of thoughts, the courage of a dissenting individual or group, and the possibility for change.

Perhaps related to this, Menexenes have a strong creative streak centred around the notion of a holistic shift where an entire systems flips into something new and different. While they don't have laughter, they can appreciate jokes in an aesthetic, meditative manner. The effect is best composed to a zen koan — and indeed Menexenes tend to lump jokes and koans together as having the same poetic affect.

Menexenes highly social animals. In their ancestral state, as many as a thousand individuals might work on a web. Their Dunbar number is in the region of 600, and they have a strong social intelligence. Their fiction can seem ponderous and baroque to other clades, with relations between the main characters sketched out fully in all their permutations, taking into account many subtle shades of alliance, antagonism, and manipulation.

Some universals of social interaction include: Pallium wrestling, grooming (many animals in the biosphere host parasites in their pallia), partial sexual contact, and a form of play by creating small thread structures to interact with.

Having evolved from a species working together continually on a single structure, Menexenes are exceptionally good at co-ordinating their activities. Animosities and feuds will rarely stop individuals from working together if they see the need.

A common activity is the chatter-school — often used as a form of decision making. Up to a hundred (sometimes more) Menexenes gather in relatively close proximity, so each individual is sharing its outer pallium with eleven of twelve neighbours. All participants speak with both plasma waves and by shifting their mutual pallia. The process at first appears quite chaotic, with all individuals throwing out suggestions, opinions, and preferences. As an individual hears other opinions, it repeats them with greater or lesser intensity depending on its agreement. Eventually, they come to a consensus. Given the high bandwidth of pallia contact, plus a number of effective heuristics, a decision accounting for all preferences can usually be reached in less than an hour.

By nature, Menexenes tend to be aggressive and hierarchical. In their prehistory, individuals would express dominance by pallium wrestling and appropriating the webs of others. Modern Menexene culture works to counter most of these trains, and is largely peaceful and egalitarian. However, since the diaspora, some groups have abandoned their cultural background and adopted more hierarchical societies.

Image from Steve Bowers | |

| Menexenos, with YTS 1499-0101-4B in the background | |

Society

On Menexenos

There are two core units to Menexene society on their homeworld.The first is the community, a group of 500 to 1500 Menexenes living together in a single structure (or group of nearby structures). There are a few common traits across nearly all communities — individuals may freely leave, there is obligatory hospitality for visitors, and decision making occurs by chatter-school mediated consensus. Beyond that, there is a huge amount of variation. Communities may be communal or individualistic or anywhere between; they may be organised around specific lifestyles or belief systems; they may be withdrawn or open.

It is common practice for communities to send delegates to one other — chosen either by lot or chatter-school. A delegate is more than a representative, but is meant to actively participate in the communities culture. Generally, communities share delegates with their close neighbours, plus other more distant communities they have a close relationship with.

The second is the guild. A group of Menexenes from different communities may associate together based around some special interest. Here, too, there is a huge amount of diversity. Guilds may be simple hobby groups, secret societies, or gigantic industrial co-operatives. The only universal is free association. By nature, a guild may have members from many different communities.

The result is a society made of a web of complex cross-links and relationships. An average Menexene may live in a community, have spent some time as a delegate in other communities, and be a member of dozens of guilds. Xe will have a a degree of loyalty to all these institutions, and a vested interest that they don't come into conflict.

There are other spaces in society, of course. Some communities are isolationist, and rarely interact with outsiders. Some Menexenes live alone in webs they have made themselves, and only participate in guilds. Others may be hermits. The most important "outsider" social class, though, are travellers. These Menexenes simply move from community to community, taking advantage of the hospitality convention. Travellers compose between five and sixteen percent of the population at any given times (the lifestyle's popularity changes over time). Most help out at whatever community they are visiting. Travellers are considered another essential link binding society together.

Direct economic relations between communities take many forms. There may be direct trade, gifts and free provisions of services, or any degree of reciprocity between. Some organisations co-ordinate with guilds to help them do useful work. Other times, communities and opt to provide some degree of obligatory labour on a rota. Menexene society is neither propertarian or communal as such; rather, there are degrees of territoriality, ranging from the entire planet, through the community, down to the individual.

Finally, nearly all communities and guilds co-operate as part of the Great Web, somewhat akin to a world government, which administers planetary-wide infrastructure.

A final element, ubiquitous and yet at a remove from the rest of Menexene society is the anti-militia. Part army, part philosophical-monastic order, the anti-militia acts only if large scale war breaks out. Their remit is simply to act as a counterbalancing force by opposing the aggressor in a violent conflict. This system has been remarkably successful in maintaining peace across Menexenos — the last time Menexene war was in in the 1300s AT.

Society since the Diaspora

Since the diaspora, Menexene society had diversified tremendously. And yet, for the most part, the diaspora Menexenes have retained similar social structures to those on the homeworld, with a complex patchwork of communities and guilds. Against this background, they incorporate various Terragen social structures, such as exoself-mediated cyberdemocracy, autotopias, and some degree of aicracy.At the same time, the diaspora has given a minority of groups the opportunity to change social forms. These Menexenes, often renouncing their home culture, tend to revert to more hierarchical forms of social organisation — despotisms, theocracies, and strong aicracies.

Culture

A common theme winds through Menexene culture, from popular music to literature to religion. In may be summarised as the general malevolence of nature. In this cultural worldview, everything is on the verge of collapsing. Friendships stand ready to turn into mistrust and betrayal; great artworks to fall into disrepair; civilisation to decay into anomie. Menexene culture seems haunted by, as one poem puts it, the loss of all magnetised things. The details vary: It may be an actual malevolence, or simply a seeming obsession with tragedy. It may be a violent, catastrophic end, or simply a slow grind which wears down everyone and everything. (In fact, when Menexene science discovered entropy, it was quickly seized as a cultural concept, even being worked into some religions.)It remains a matter of debate why such a peaceful, long-lived society should have such an aggressive cultural outlook. There are two dominant schools of thought among Menexenologists. The physicalist view holds that it is simply an expression of the environment the Menexenes find themselves in. They encounter nothing solid. The only structures are, like the biosphere itself, composed of MDH structure and vulnerable to decay without active upkeep. Hence this theme finds its way into all cultures. Conversely, the counter-power view holds that this obsession with decay is in fact a naturally-arising societal strategy. Menexenes channel their violent, hierarchical urges into a metaphysical worldview rather than society itself. And further, the notion the world is intrinsically subject to decay and violence helps inculcate individuals with a sense that they must actively work for stability and peace. Hence the violence expressed in culture is a necessary counterpoint to the peaceful Menexene society.

Religion and philosophy

Menexene religious thought displays all the hallmarks of a long history: Thousands of schools of thought, schisms, almost forgotten minor cults, reformations, counter-reformations and revival movements, syncretisms, theocracies, long periods of legally mandated belief, fads and static multi-millennia monastic orders. A few universal traits emerge: Menexenes are relatively less likely to posit deities, especially omnipotent ones, instead tending towards impersonal forces and complex, flamboyant cosmologies. (This is not to say that there are no deities in Menexene religions — simply that they are rarer and have less staying power than other forms.)Modern Menexene society stands in the shadow of three broad classes of religion.

The silent way posits an ineffable, inscrutable, all-pervading substance to the world. It is. In a sense, analogous to the Tao. But rather than being positive, it is fundamentally inimical to everything. Its uncountably infinite claws are in everything, subtle as a magnetic whisper, but present nonetheless, slowly tearing down all possible joy and achievement. What is to be done? Simply to live in opposition to it, wringing out what ever joy one can from life — but at the same live in line with its unbeatable logic. (In fact, the Menexene word for entropy derives from the silent way.)

Afterbirthism is distinguished by its cosmology. At some distant point in the past, a perfect universe, free of decay, suffering, uncertainty, shame and cruelty was created. That universe is not this universe. This universe is merely a byproduct, a sort of afterbirth for the perfect universe. It is destined to slowly rot and decay into nothing. The perfect universe is forever unattainable. Afterbirthism is notable is being one of the very few Menexene belief systems that contains the notion of a perfect universe. (Afterbirthism is, in fact, a misnomer. Menexene reproduction does not create an afterbirth. The actual metaphor is derived from the seed-husks of coiltrees, which even after they have created a new tree remain noxious and inedible as their stored energy slowly decays and they dissipate.)

The Teatro Grottesco has a large and complex literary background. Close to three thousand stories of varying lengths depict a rogues gallery of spirits and daemons. These characters, capricious, violent, sadistic, and sometimes insane, make up a pantheon of sorts. They variously trick, torment, and hex one another — and the population of innocent (or not so innocent) Menexenes. There is no consistency to the canon — characters die and are maimed in one story, only to appear whole in the next. Whether such characters are actually real, or merely metaphors or Jungian archetypes, is a matter of vociferous debate in the Teatro's history.

None of these three religions are monolithic — they include a variety subtypes, some of which are virulently opposed, some of which are long-extinct. Further, they no longer have any significant power as religions themselves — they have since been supplanted by community-based belief systems, many of which include a rationalist/scientific bent. However, they are powerful part of the cultural background, their influence woven into ordinary language, literature, imagery, and many cultural practices.

Language and literature

Menexene languages have a different deep structure to human languages. They construct sentences by chaining together dozens or even hundreds of verbs, with inflections or word order denoting relations, moods, and qualities. All words are subject to inflection in this way — even names and personal pronouns need an inflection for tense.The Menexenes' environment makes writing difficult. It is impossible to simply make marks — one must construct an MHD structure in the metallic hydrogen. And old and primitive form of writing, only used by a few cultures, is made by knotting together web threads in complex ways, storing the information in topology. A more recent form stumbled on a similar method the Menexene genome: They create a thread of magnetic bottles, each filled with a different contaminant — effectively a sort of smell/taste form of writing. The impurity method of writing is more compact than using threads, but it is still bulky: A single sentence can be several metres long. A novel can take up several times as much volume as a Menexene. Further, impurity-writing becomes depleted with each reading, and must be occasionally topped up, or the information will be lost.

A more recent advance produced recordings: Large structures, when electromagnetically stimulated by a listener, can produce plasma waves similar to a Menexene voice, or variations in its magnetic field equivalent to those for intimate communication. An advantage of this method is that the listener, by stimulating the recording, recharges it and prevents it from dissipating.

The relative difficult of writing has effected Menexene culture in many ways. First, even in the current era, there is a strong tradition or oral recitation and memory techniques. Second, Menexene written language invariably bears little relation to "spoken" language, being far more terse.

Third, libraries are of great importance in Menexene culture. These immense structures are seen as the strongholds of civilisation. They are connected directly with the global energy grid, and have large capacitor backups. Many store information with multiple redundancies, and a small army of devoted librarians ensure the stored works do not dissipate.

Menexene poetry often takes advantage of the multiple types of plasma waves. Alfvén waves and acoustic waves represent different channels (with different dispersions), allowing counterpoint or ironic commentary. Combined, then form magnetosonic waves, which can be used as a special synthesis. Being able to use all these modes together takes considerable poetic skill. Further, the waves follow field lines — so the field structure around a recitation is an essential element of the "acoustics", which itself can be manipulated to add another aspect to the poetry.

Thematically, many Menexene works are ensemble tragedies: A group of friends is revealed, their relations carefully delineated. Tensions among the are ratcheted up as the plot progresses, leading to a dizzying array of lies, hidden betrayals, and simmering rivalries. At last, a single incident causes all these tangled tensions to snap together, leading to catastrophe.

Web-art

Since all Menexenes have a natural ability to spin webs, creating "sculptures" out of threads forms fundamental class of art in all Menexene cultures. These range from the small, everyday decoration and idle creative expression, to immensely prestigious structures, some of which may have hundreds of contributors working together. In its larger form, web-art becomes a sort of architecture, forming large-scale structures.Pallium decoration

Pallium decoration is somewhere between clothing, body modification and dance. Menexenes hold their pallia in certain aesthetically-pleasing patterns. By adding smaller organisms in certain places, they can enhance the affect, and a certain degree of training is necessary to learn the more complex forms.Many communities have their own variation of pallium decoration, and, of course, there is the occasional cross-cultural fad.

Chatter-dancing

Chatter-dancing is related to the chatter-school. A group of Menexenes gather, sharing their outer pallia. However, the point of chatter-dancing is not to talk or reach consensus. Indeed, the interacting magnetic fields may not even hold semantic information. Rather, it is simply a form of play — the Menexenes enjoy the close contact and interaction. As the name suggests, it is analogous to dancing, with all partners contributing to and enjoying a shared movements. Many forms of chatter-dance are enhanced by the addition of "music" — artificial, externally-generated rhythmic magnetic fields that interact with everyone's pallia.Science and Technology

In a sense, all Menexene technology is a form of biotech: It is based on the same dynamic MHD structures as Menexene life. There is simply no other possible technological base in their environment. Anything that is not dynamically sustained will dissipate, so even the most primitive technology required energy.The earliest Menexene technology — roughly equivalent to the palaeolithic — was made from webs and worldtrees. A number cultivated of trees bound together by webs could form a village, or even, as population numbers grew, an entire city.

With training, the early Menexenes were able to generate more complex structures with their spinnerets. With more effective cultural transmission (eventually aided by magnetic braid-writing), they began to develop an extensive repertoire of techniques, learning to create more and more sophisticated structures. Added to this was animal husbandry with selective breeding and modification of the worldtrees into more effective structures.

Global technology

At the time of contact, Menexene technology was defined by three global systems covering the all the habitable regions of the core. They are powered directly by convection currents and the planet's spin.The energy/food net extracts this energy directly, transports it by means of electric currents, and stories it in giant capacitor banks. At the point of use, it directs energy into magnetic tension in special structures, from which any Menexene can feed directly.

The global circulatory system is a vast network of fluid flows directly along field lines that serves as a universal and relatively fast transportation network. Its widest arterial routes are over five kilometres across, while the smallest are less than a hundred metres. A Menexene may simply swim into the flow through gradual transition zones. Or xe may take a vehicle (like animals, vehicles use jets of hydrogen for thrust) and gain ad added velocity boost.

The telecommunications net uses modulated electric currents for long-range communications and broadcast plasma waves for short-range. Most Menexene computers are analogue, using a complex logic based on the topology of field lines, though they do have some digital computers for special purposes.

Mathematics

Menexenes have little intuitive sense of numbers. Rather, their entrance into mathematics came through topology and something resembling group theory. Their mathematical texts tend to use visual proofs (albeit expressed in three dimensions through magnetic braids or fluid flows). They did learn about numbers eventually, though even there, they discovered the distinction between rationals and irrationals before integers.Planetology and Cosmology

By the time of contact, the Menexenes had developed an accurate model of Menexenos, including its composition and diameter. By observing and manipulating the planetary magnetic field, they had deduced the existence of stellar wind. But thereafter, their investigations were hindered by their inability to get themselves or any of their instruments out of the core. Many theories were put forward about the source of the stellar wind, some of them quite close to the truth, but they were underdetermined by the observational evidence. Aside from stellar wind, there was no evidence about what lay outside Menexenos. Most scientific views simply proposed there was nothing else — no more than vacuum, bounded or infinite.History

Pre-contact

Menexene recorded history begins around 14,000 BT. The evidence suggests that this was not the start of their civilisation — technology at the time was already relatively advanced — but rather, the emergence from a dark age. Fragmentary evidence points to a catastrophe and subsequent dark in which almost all written records and artefacts were lost.The next thousand years saw an emerging renaissance in the southern hemisphere, during which the earliest great libraries were constructed. An advance in power-storage technology allowed the Menexenes of this era to traverse the deserts between forests of worldtrees and explore their world. Eventually, in the 13,000s, a movement to spread libraries across the whole core grew into an immense caste-based despotism — the Archival Empire — that covered most of the southern hemisphere, and held several outposts across the core.

The Archival Empire, under growing strain from its caste system and the northern barbarian webs, fell victim to a number of states from the north in the 12,600s. These new states were effectively the same in ideology and social structure as the Archival Empire, and largely carried on its words. For close to two millennia they politicked and warred over differences in method, but nonetheless managed to cover the planet with libraries

In 10,200 BT, the Archival States had split into two great power blocs. The ensuing war killed close to half the population and destroyed many libraries. But a universal cultural value of preserving information stopped the growth of another dark age. The resultant decentralised civilisation began with new peaceable values. A loose democratic federation grew slowly. At its height, the Calm Federation governed close to a third of the core, and extended hegemony over the rest.

Through the 7700s, a number of religions from the ungoverned regions — amongst them Afterbirthism — grew in prevalence, and in turn fragmented due to doctrinal difference. A series of religious and anti-religious conflicts led to outright war, and another quasi-dark age. During this period, the most feared force was the Shadow Front — an ideology which explicitly turned against the old Archival ideology and was in favour of letting libraries decay. While the Shadow Front never achieved significant power, it destroyed many libraries through the core. The power-storage methods were lost, and the great deserts became impassable once more.

In the upper layers of the core, a brief union of states under the banner of Afterbirthism rose and fell in the 5000s. This period also saw the emergence of the Silent Way, which came out of a monastic movement trying to protect the libraries. The deeper regions, meanwhile, saw a short lived chain of amoral conquerors across the web-villages, which gave rise to the Teatro Grottesco religion.

Eventually civilisation rose again from the upper core, and redeveloped the means to cross deserts. It sent out a wave of colonisations to the deeper core — but the deeper core proved technologically superior in other areas, and instead conquered the upper core. In time the colonies rebelled, and another chain of religious wars followed.

The first activities of the anti-militia began the 3000s. Their first few attempts were easily routed, and all militia members killed, but the romance of the resultant martyrs, and a general exhaustion with war, led to a growth in its popularity. It took close to a thousand years, but the wars began to die down as would-be conquerers ran into a heavy resistance.

The nations still competed by means of complex espionage, assassinations, or industrial might. Eventually, in the 1600s BT, widespread dissatisfaction with living conditions led to a series of secessions and revolutions. The resulting wars brought in the anti-militia again. The long term result was the fragmenting of the old states and rise, ultimately, of the community system.

The communities, stabilised by a cross-linked network of guilds, became a power alongside the old empires. Their fortunes rose and fell. Sometimes, a group of them would ally and form a new state. But in the long run, the system proved stable: The empires fragmented at a greater rate than the communities allied into states. Those empires that didn't fragment saved themselves by enacting widespread reforms that eventually made them indistinguishable from the communities.

The last great Menexene war arose in the 1300s AT, following the rise of an Afterbirthist theocracy. Though it conquered a large portion of the core, it eventually fell victim to internal tensions, subversion from the communities, and relentless pressure from the anti-militia.

Contact

In 8862, ships from the Paideia Mission (a small exploratory member polity of the Orion Federation) reached Socrates 471. From a distance, it seemed the system held little of interest — it was to be used a resource base. However, upon arrival the Paideians noticed an inexplicably strong and dynamic multipole in Menexenos' magnetic field.After several years of careful study, the Mission discovered the Menexenes, and initiated contact by manipulating the magnetosphere. Soon, higher bandwidth communication was achieved by stringing cables in the lower atmosphere.

First contact came as something to a shock to the ancient and conservative Menexenes, who had long discounted the vacuum outside as empty and anathema to any sort of life. Terragen culture and history was quickly disseminated through the communities.

As they learned more, the Menexenes became more cautious. The cosmology of stars and galaxies had an almost religious tinge to it from the beginning. Terragen civilisation was young, incontestably powerful, and seemed to be driven forward by an endless series of destructive wars. Histories of previous civilisations, seemingly extinguished at the height of their power, seemed to indicate the Terragens could be destroyed at any moment — and the Menexenes along with them.

Possibly worse, contact seemed to be disrupting Menexene society from the inside. Religious groups centring on a Terragen mythology sprung up, some of them worryingly expansionist. Elsewhere, xenophile groups pushed for integrating with the Terragens.

Outside, after a delay of some twenty years, news of the Menexenes reached the Nexus, and they quickly became famous. Menexene drama-tragedies were adopted into a variety of media. A fad for neogenic ecosystems based on similar principles became popular — and several groups set out for Socrates 471 in search of the real thing.

It would impossible for the Menexenes to leave the core intact. The Paideia hyperturing after some effort, created a MHD-based destructive uploader and engenerator, so the more adventurous among them could visit the outside, and select Terragen sophonts could visit the core. There was a brief clamour among the more adventurous Menexenes to be the first to visit the vacuum (if only in virtual form).

As the cultural exchange progressed, discussions swept the core about whether or not it was safe, or even avoidable, to join Terragen civilisation.

At last, after many thousands of chatter-schools, a consensus was reached. It appeared — given the sparse evidence of the Jacks — that the cores of gas giants were safe from the predations of whatever stopped powerful interstellar civilisations, at least so long as they kept to themselves. So the Menexenes decided they would close Pandora's box as best they could, and retreat from contact.

The xenophile faction would be permitted to upload and leave, thereby relieving some of the social stress of contact. The vast majority of Menexenes who chose to remain requested Caretaker God assistance over the Known Net. As a parting gift, the Menexenes provided a copy of their cultural database, plus a full listing on Menexenos' biota. The Paideian Hyperturing in turn offered a small cachet of advanced MHD technologies the Menexenes were willing to accept, including life-extension and other medical advances, and more stable information storage mechanisms.

The Menexenes who chose to leave — a little over 600,000 — were uploaded into a virch environment provided by the Paideians.

The request for a Caretaker God was swiftly if tersely answered: A halo drive ISO arrived in Socrates 471 in 8940 and began setting up a restriction swarm. Though uncommunicative, it waited long enough for the Paideian Mission, the xenophile Menexenes, plus various groups who had just arrived to meet them, to leave.

The Diaspora

The loss of Menexenos itself was a blow for those who had come to see it, but there remained the xenophile Menexenes in their virch, housed in the adjacent system, who were both willing and eager to make contact. The xenophile group quickly diversified, spreading through the Terragen Sphere. Some chose to remain virtual; others sought out Jovian planets they could colonise. Between the late 8900s and the early 9000s, Menexenes became a regular sight throughout the civilised galaxy, talkative to the point of being garrulous and filled with brio. (This, of course, was partly a selection effect — modosophonts naturally saw more of the most energetic Menexenes.Menexene Pantropes

Menexene biology, based on MHD processes in liquid metallic hydrogen, limits them to Jovian interiors. Few other environments can sustain enough pressure to turn hydrogen into a liquid metal.In response, many diasporic Menexenes in the Terragen Sphere live as virtuals or have been engenerated into other gas giant interiors. Menexene Pantropes, however, have become embodied using magnetohydrodynamic systems in other conducting fluids, which allow them to retain a broad resemblance to baseline Menexenes. The two most common types are Plasma Menexenes and Iron Menexenes.

Iron Menexenes are based on molten iron with embedded impurities. They are slightly smaller than baseline Menexenes, with a pallium length of 18 metres, and require specialised habitats with magnetic fields, electric currents, and a temperature of 2000 K. In the Perseus Arm, Iron Menexenes have formed an association with provolved Rheolithoids, the former living in the core and the latter in the mantle of artificial high-temperature planetoids.

Plasma Menexenes have a biology based on low density hydrogen plasma. Because of this low density, they are much larger than baseline Menexenes, having a pallium length of approximately 64 kilometres. Some live in specialised habitats which contain the plasma and supply magnetic fields and electric currents. Other are capable of living in open space. Space-dwelling Menexenes require a network of microscopic superconducting threads inside their bodies to supply energy and contain the plasma. Because they are vulnerable to disruption, most also use the network as a form as Direct Neural Interface to maintain a backup copy.

By the Current Era, many of the xenophile Menexenes have integrated so fully into Terragen civilisation as to become part of it. There remains one significant exception. The Helium Expansion, founded by some of the more conservative xenophiles, is predominantly Menexene polity advancing in the Auriga sector. Its attention is mostly limited to suitable Gas Giants, linked by Among other things, the Menexenes of this polity have had some productive contact with some Soft One worlds regarding matters of long-term archival management and civilisational survival.

Articles

- First Exocore Bordered Corpus - Text by Liam Jones

Independent polity formed by the group of eccentric breakaway Menexenes "Association-With-Greater-Civilisation Guild" aided by the archailect Synergenesis. - Garden Worlds - Text by The Astronomer, Steve Bowers 2020

Worlds that support a complex biosphere and macroscopic life forms. - Secrets Inscribed in Caustics - Text by Liam Jones

Secrets Inscribed in Caustics is a largely abstract environment designed to accommodate many alien mindform types - Socrates 471 system, The - Text by Quantum Jack

Triple system containing the Menexenes' home world

Related Topics

Development Notes

Text by Liam Jones

Initially published on 23 May 2006.

amended June 2013, expanded in April 2018, and 'Menexene Pantropes' section added December 2023 by Liam Jones

Initially published on 23 May 2006.

amended June 2013, expanded in April 2018, and 'Menexene Pantropes' section added December 2023 by Liam Jones

Additional Information