BY LETTER

Proteus (Clade)

Image from Steve Bowers | |

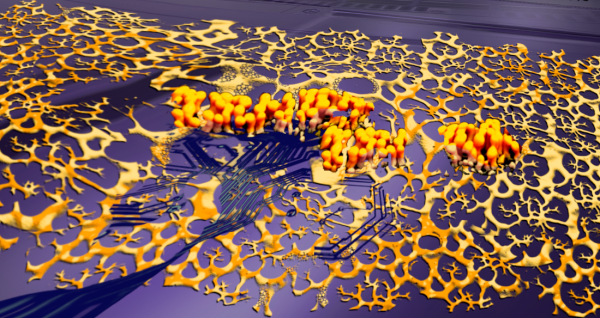

| A clade Proteus plasmodium, showing sporangia and a hylotech interface allowing the Proteus to interact with, and control, local technology. | |

Ancient clade of sophont slime molds, believed to have been fully provolved as early as 4200 AT during the middle Integration Era and commonly found throughout the Terragen Sphere in the Modern Era.

Overview and History

Naturally-evolved slime molds are single-celled eukaryotic organisms belonging to several polyphyletic taxa, similar in many ways but distinct from fungi. Members of the class Myxogastria are known for their ability to form macroscopic structures called plasmodia, which resemble sprawling networks of branching vein-like tubes, which can crawl across surfaces in search of food. These consist of millions of cells whose membranes have fused together, evenly distributing cytoplasm and nuclei in a configuration known as a syncytium. A plasmodial slime mold can move as fast as several millimeters per second, and may grow to cover several square meters in area and mass up to several tens of kilograms.The behavior and movements of plasmodial slime molds have been a source of fascination for biologists from the time of Old Earth into the Modern Era. Many have remarked on the seemingly intentional nature of their movements, yet they lack anything resembling a brain or nervous system, instead relying on simple algorithms to find paths of least resistance and navigate around obstacles. They can efficiently solve mazes by exploring many paths at once, quickly form topological networks linking multiple nodes with maximal efficiency, and if they are broken apart the individual pieces can find their way back to one another to re-group. They even possess a limited form of memory, noting locations where they have previously detected food by encoding detection events as localized changes in the thickness of their tubules, retracing their "steps" or avoiding doing so by laying down chemical trails that they may later choose to follow or avoid, and acting in anticipation of future changes if subjected to repeating patterns of stimuli. Slime molds have long been regarded as a classic example of emergent behavior; many aspects of their biology served as models during the early development of swarm nanobots.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given this history, slime molds were among the earliest targets for provolution by Old Earth geneticists and bioengineers, although they naturally proved a far greater challenge than mammals or other vertebrates. Many attempts were made during the first few centuries AT to breed slime molds with enhanced problem-solving abilities, mainly by using CRISPR-Cas gene editing to tweak various genes related to chemotaxis and electrochemical signaling. While these were moderately successful, they fell short of achieving anything close to even the most basic vertebrate-level intelligence. In parallel with these efforts, several research groups attempted to build biological computers using slime molds as a substrate, and enjoyed far greater success in this endeavor, with numerous models of slime-mold-based bio-computer entering the consumer market during the SolSys Golden Age.

Many of the major difficulties facing early slime mold provolution efforts were eventually addressed by the late pre-Technocalypse (c. 520 AT) hyperturing gengineer known as KISMET, who at the time was pretending to be a sub-turingrade AI to avoid arousing the suspicion of eir baseline human handlers. KISMET saw the potential for slime molds to be a new form of intelligence, one with a nearly unlimited capacity for intellectual growth and development - much like KISMET emself and other contemporary AIs. E saw that the problem facing eir baseline human gengineer handlers, who had been trying and failing to provolve slime molds for several decades, was that the slime molds had no system for maintaining persistent connections that could form the basis of true memory and learning; despite their passing resemblance to a map of a nervous system, their plasmodial networks were too fluid and their structures too transient to be able to constitute a true animal-style "brain" or neural net. Moreover, the baseline gengineering research group fundamentally lacked the capacity to envision how such a neural net would need to be arranged even if they managed to solve this problem.

For KISMET, addressing both of these seemingly insurmountable challenges was a laughably trivial task. Still masquerading as a "dumb" subturing expert system, e gradually proposed a series of modifications to the slime mold genome that would facilitate the maintenance of connections in the plasmodial network, as well as amplify the slime molds' existing systems of chemical and electrical signaling. Within two years, e had achieved what eir nearbaseline handlers could not: a slime mold capable of learning and retaining complex information, planning ahead when attempting to solve problems, performing basic arithmetic, and communicating with its handlers via words spelled out by its plasmodial network. Several of these developments were wholly unanticipated by the baseline human research team, much to their shock and KISMET's amusement.

It is unknown what exactly happened in the roughly three and a half millennia following this breakthrough, but during the middle Integration Era (c. 4200 AT) multiple populations of fully-sophont slime mold provolves began appearing throughout the burgeoning Sephirotic Empires. This nascent clade was given the name "Proteus," in reference to a shape-changing deity from Old Earth Ancient Greek mythology.

Over the following millennia, members of clade Proteus would spread throughout the Terragen Sphere, often as stowaways within the waste-collection systems of habitats and crewed vessels, later hiding themselves in the soil and leaf litter of forests on terraformed colony worlds. Today they can be found in most of the Sephirotics and beyond, particularly within the Zoeific Biopolity Communion of Worlds, Sophic League and Utopia Sphere. Unaugmented individuals tend to be fairly reclusive and form their own isolated communities, partly owing to the difficulties in communication between themselves and most other sophonts, but many augmented individuals have integrated into other modosophont societies.

Many have noted similarities between members of clade Proteus and the extinct species of xenosophonts known as the "Lhagharians" (HIE-072-CZE), which like their extant non-sophont relatives on Lhagharia (commonly referred to as "gunks") were amorphous, colony-based organisms with several traits in common with Terragen slime molds. However, many details of their biology and biochemistry differed substantially from true slime molds, as well as Terragen life more broadly, and they appear to have used a radically different system of neural/cognitive architecture than that used by Proteus.

Anatomy and Traits

At a glance, most members of clade Proteus are outwardly indistinguishable from members of the baseline slime mold genus Physarum, aside from invariably massing at least one order of magnitude more than their ancestors; an "individual" Proteus of nearbaseline human intelligence typically masses around 100 kilograms. If one looks closely, they will also notice that the plasmodial network that makes up the Proteus is not entirely fluid and changeable: among the sprawling, ever-shifting network of tendrils, there is a localized pattern of tubules which remains mostly constant in layout, with minor changes taking place around the periphery. This is the "brain" of the Proteus, which generally holds its shape regardless of how the rest of the "body" reconfigures itself. When a Proteus needs to move quickly or pass through a narrow opening, this arrangement of tubules will compactify itself into a tight knot, vaguely resembling a slimy vertebrate brain, which is elastic enough to be compressed or jostled without breaking its topology. The rest of the plasmodial network is entirely mutable: a Proteus may spread itself out over a large area, its lacy tendrils forming a layer as thin as a sheet of paper, or it may condense itself into a single, viscous blob. Like their ancestors, they tend to be very brightly colored, usually being a solid neon yellow or orange in color.Like their pre-sophont ancestors, Proteus do not have anything resembling muscles or a skeletal system; the tubules which make up their plasmodia are incapable of pushing, pulling or flexing motions, and their cell membranes are in their default state flexible and fragile (although some cyborgized individuals incorporate nanobots into their structures to enable these types of movements and provide added structural support). However, as needed, they are capable of secreting a cell wall made of cellulose to reinforce their membranes and give their tubules greater strength and rigidity; baseline slime molds only exhibit this behavior when producing spores, which are coated in cellulose for protection. By directing the growth of their network using signaling molecules called acrasins (this growth can occur at a rate of up to several centimeters per second, an order of magnitude faster than in baseline slime molds) and secreting a thick cell wall around the new growth, they are capable of growing against the force of gravity, and can lift even relatively heavy objects by slowly growing vertical extrusions underneath them, or push objects by growing toward them at a horizontal angle. Given enough time, they may even draw their entire body upward into a free-standing form with "legs" and other appendages, capable of a very slow and deliberate walking mode of locomotion, and interacting with their environment using lightweight, honeycombed pseudopods or "hands." This is generally considered to be more trouble than it's worth and is rarely done, with the most common use-case being to unnerve nearbaseline humans and members of other sophont terrestrial vertebrate clades, typically for the Proteus' own entertainment.

Baseline slime molds do not have "senses" in the way that most animals do; instead exhibiting simple behaviors like chemotaxis (movement toward or away from certain chemical triggers), phototaxis (movement toward or away from light of various wavelengths), and durotaxis (preference for substrates of a given hardness or softness). In Proteus, these "senses" have all been augmented through the addition of new signaling proteins and pathways, and feed into the central processing hub, allowing them to experience a wider and more nuanced range of stimuli than their ancestors. They have also been augmented with specialized mechanoreceptor cells that grant them a vibrational sense, which allows them to "hear" sounds by picking up reverberations in the surfaces they are in contact with. If the situation calls for it, they are capable of forming simple "eyes" and "ears," consisting of organized arrays of light- and vibration-sensitive cells, which allow them to take in higher-resolution visual and auditory information; however, as with adopting a standing posture, this is usually seen as not being worth the effort. Many individuals have nano-augments that allow them to link with nearby cameras, microphones and speakers, thus enabling them to hold conversations with individuals of other clades. In the absence of these options, a Proteus can arrange its plasmodial network to form words and sentences in order to communicate visually, although this takes time and can be frustratingly slow for an interlocutor as they wait for a response.

Proteus utilize two modes of reproduction. Much like their ancestors, they may convert parts of themselves into "fruiting bodies" called sporangia, which produce spores that may be blown by air currents, carried by water or dispersed by insects or other small animals. These spores mature into motile haploid (having only a single copy of a given chromosome) gamete cells, which then seek out gametes originating from another Proteus and fuse with them to produce diploid (having two copies of every chromosome) cells. The nucleus within each diploid cell then divides, but the cell itself does not, resulting in a single cell that continuously grows larger and contains many nuclei - a syncytium, which forms the basis of a new plasmodium and a new Proteus. In baseline slime molds, the plasmodium is the penultimate stage of the life cycle, followed by the formation of sporangia and the subsequent death of the colony, but in Proteus the plasmodium stage lasts indefinitely and sporangia may be produced repeatedly and at will.

The second mode of reproduction typically involves a mature Proteus dividing its central "brain" into multiple segments, each configured as a partial or total copy of the original pattern of tubules. These will each then serve as the basis of a newborn Proteus, each of which retains the memories of the "parent". This mode has been likened to the process of forking commonly used by many biological and non-biological sophonts, with each new Proteus being considered a bioxox of the original. If desired, a Proteus may also choose to give each of its "children" only a subset of its memories, or in rare cases none at all; the latter is regarded as effectively being a form of suicide. It may also interface with another Proteus to merge their neural networks with each other, subsequently becoming a new individual blending attributes of both "parents," splitting into multiple such individuals, or budding off one or more composite "children" before separating once more into their original configurations.

Image from Worldtree | |

| A Proteus uses several tablet screens to show emotions more relatable to its mammalian sophont followers on social media during a 'selfie' session in the woods | |

Psychology and Cognition

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Proteus have a very "fluid" sense of identity, as they tend to frequently split themselves into multiple pieces that accrue divergent experiences before fusing together once more. Though these pieces share memories with one another and/or the initial whole upon fusion, they do not fully re-integrate right away, instead remaining semi-independent loci of cognition and perspective that gradually blur into one another over time and eventually merge into a single, cohesive consciousness. As such, at any given time a Proteus may be effectively a coordinated group of "individuals" sharing a single "body," a seamless undivided mentality, or anything in between. The degree of division, or lack thereof, within the subjective mental state of a Proteus is usually reflected by the frequency with which they refer to themselves using first- or second-person pronouns when conversing with other sophonts.Furthermore, as a result of this constant splitting and merging of personalities, a Proteus may not regard themselves as being the same individual that they were days or weeks ago. When re-integration occurs, no one personality can claim ontological privilege over any other (i.e. each feels itself equally to be the continuation of the original Proteus, while the original Proteus itself no longer truly exists), but as the personalities blend together over time, there will usually be one that ends up rising to the fore and becoming the center of perspective, while still taking on some characteristics from all the others as they fade into it. This new personality will likely have diverged significantly from the "parent" even prior to re-integration, and they may differ significantly in viewpoint, subjective preferences/tastes, and so on from their progenitor. Though they will necessarily retain all the memories of their component parts, they will thus very commonly - though not invariably - describe themselves as being a wholly different person from their "original," in a similar (though not identical) sense as a nearbaseline human child is a different person from their parents.

As with most sophont clades, Proteus exhibit a wide diversity of personality traits and behaviors, made even more diverse by the aforementioned frequent rearranging of their cognitive architecture. They are often found by others to be playful and inquisitive, sometimes verging into nosiness, as they will use their mutable anatomy to infiltrate the private spaces of other sophonts and eavesdrop on conversations. They are also given to practical jokes, such as surreptitiously moving objects using their plasmodial network so as to cause confusion or surprise on the part of other modosophonts, or adopting shapes designed to discomfit modosophonts unaccustomed to morphologies dissimilar to their own - or, alternatively, to the sight of a sophont slime mold attempting to take on a morphology resembling their own.

Due to the modularity of their central "brain," a Proteus can augment its intelligence and memory capacity simply by growing larger and adding new elements to its cognitive tubule network. Many individuals have even managed to breach the First Toposophic Barrier in this way, with no augments or other technological assistance being required, though they still typically require guidance from a transapient mentor or an Ascension Maze in order to make a complete and safe transition to S1.

Cultures and Societies

Proteus tend to live as loosely-associated groups on the peripheries of other modosophont communities, but on occasion they have formed organized societies of their own; the Paludial Gaian world Myxus in the Zoeific Biopolity and the terraformed NeoGaian world Understanding in the Sophic League host two of the largest and oldest Proteus cultures.Related Articles

- Bradychronic Plant Provolves

- Brain Kelp

- HIE-072-CZE (Lhagharians)

- Post-provolve - Text by M. Alan Kazlev

An provolve who has attained to S1 or above. They can be as varied and diverse in origin as provolves themselves. - Provolution Timeline

- Provolved Reef squid

Appears in Topics

Development Notes

Text by Andrew P.

Initially published on 02 October 2024.

Initially published on 02 October 2024.